Who put the paths there?

There is a story told of an architect who was commissioned to design a new university campus. After the construction of the buildings had been completed, the final piece of work was to lay the paths that would connect the various buildings of the campus. Before the architect had a chance to put this work in motion, the Dean of the University suggested that this final stage of the project should be left until the buildings had been occupied over their first winter. In the spring, the architect approached the Dean for permission to complete the campus by laying the paths. Before agreeing, the Dean suggested that the two of them take a helicopter flight over the campus. The architect agreed, and as they flew over he became aware of a labyrinth of tracks that had been made between the buildings by students who had walked through the mud during periods of wet weather.

‘That is where I want the paths to be laid’, suggested the Dean.

‘But that is not what was designed’, responded the architect.

‘No, but that is where the users of the campus think they will be best placed’, replied the Dean.

The logic behind the Dean’s thinking was that there is no point constructing paths where people don’t want to walk. The likelihood is that people will continue to walk on the tracks, rather than the paths. The paths might be neat and in keeping with the original design but will remain unused, whilst the buildings are likely to have mud trampled through them whenever it rains.

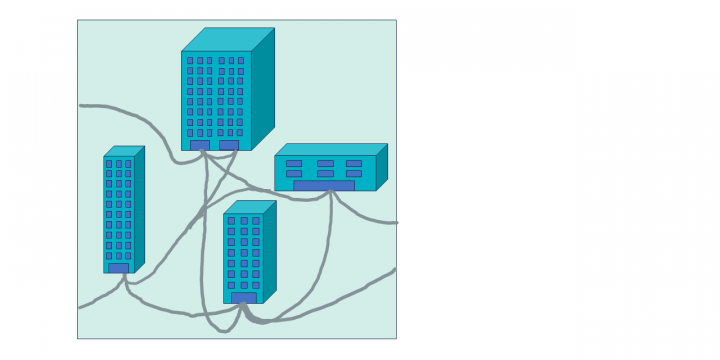

This story often resonates with me when I am working with organisations who are transitioning through change. It is important to have a clear plan at the outset of any change initiative. The need to plan every detail from the outset, to work out where the different elements need to be placed, gives people a direction of travel, and allows them to ‘buy in’ to what is being proposed. However, often little attention is given to consider how these various parts fit together (the relationships that link together individuals, teams, departments and even whole organisations).

We don’t think in straight lines

Humans don’t think in straight lines. Consequently, the assumption that people relate to each other in a linear/cause and effect way is equally absurd. Of course, at the outset of change we need to make sure that the structural elements are in place (the buildings). Finances, adequate human resources, etc. need to have been considered. But, what is of equal importance is the relationships that exist between different elements of the change strategy. How does the finance department interact with the HR professionals? What kind of relationships exist between the production department and IT? These relationships are like the paths of our university campus. If we assume they function optimally because we have drawn a line between them on the project plan, then we will be caught off guard when the metaphorical mud starts to get trampled around the organisation. Relationships are emergent in nature and will determine the quality of the systems that we end up with after the change has been designed, constructed and occupied.

I am, of course, not talking about the physical environment but the psychological environments that are central to any successful change. When organisations are planning change they nearly always begin with the structure (the functional nature of the finished design, the policies and procedures, the endless terms of reference for how groups and teams need to work together). It doesn’t matter how neat the paths are, if people don’t use them (and they won’t) the finished design just gets really muddy. However, in order to not loose face that our design isn’t working, we employ a team of cleaners to keep the mud out of the buildings (more resources and time being spent).

What was the change for in the first place?

The worst part of the story is that often we don’t need to construct a new building in the first place. I often observe organisations creating structural change as a way of not having to focus on developing more appropriate relationships.

‘The quality of a system is determined by the quality of the relationships in that system’ (Paul England, 2019)

The starting point for any change is that we want to achieve a different (or better) outcome. However, organisations can spend huge amounts of money designing new structures to find themselves arriving at the same outcome. Moving people into new positions and creating new organisational charts that are underpinned by the same people having the same relationships usually only creates a lot of unnecessary expenditure for little benefit. I listen to senior managers justifying the cost and psychological upset of change to move a ‘troublesome’ member of staff to a different place in the organisation, only to discover that nothing fundamentally alters. Spending time developing cultures where honest conversations can take place and meaningful relationships can emerge will often create the changes we want with very little expenditure. But, the structural change means we don’t have to have the difficult conversations or invest time in relationships; it just moves the ‘problem’ somewhere else, for someone else to deal with.

Creating new cultures

The fundamental problem is that our Western European culture is fixated with building new and better structures (structural systems) with little attention being paid to the people who are essential to operating these structures (dynamic systems), and when it doesn’t go quite how we want it to, we employ more ‘cleaners’ to desperately try and keep the building clean. More people, designing more governance, more change experts, more HR consultants, more working parties to make sure the organisation is on track, etc, etc, etc.

We never stop and ask the question, ‘are the paths in the right place’.

‘Culture eats strategy for breakfast’

For many, this will be a familiar phrase. Intellectually, we know that ‘the way we do things around here’ is what really drives the success of any business, organisation, or system. These cultures aren’t developed in strategy, they aren’t driven from the boardroom (although senior executives should be responsible for setting and modelling culture). Cultures are developed through individuals interacting with each other. Organisational cultures change when individuals get up in the morning and decide to behave differently. It doesn’t have to be a new strategy, a new organisational procedure, a new policy; it just needs small acts of care, compassion, understanding, that are repeated over and over again. When we do this, we begin to understand what paths needs to be laid and we replace the mud tracks with paviours. The mud stops getting trampled through the buildings and so we can send the cleaner’s home.